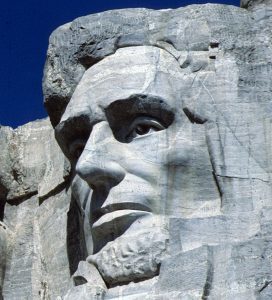

In July of 2007, I was honored to lead the Young Musicians Foundation Balmat National Orchestra Camp in a performance at the foot of Mount Rushmore. Ninety high school student musicians from all over the United States had been selected by audition for the opportunity to spend two weeks in the Black Hills of South Dakota preparing a diverse selection of music appropriate for the occasion. In addition to music by Bernstein, Rossini, Brahms, Bernard Herrmann (North by Northwest) and David Schwartz (Deadwood), my father, actor Peter Mark Richman, was to be the guest narrator for Aaron Copland’s inspiring, A Lincoln Portrait, speaking the 16th president’s words below the permanent gaze of the latter’s stony visage.

I have often thought about the leadership qualities of the four presidents whose likenesses were forever enshrined in the granite face of Mount Rushmore. Did history’s celebrated leaders conduct themselves honorably in the best interests of those whom they led? Are our presidential heroes all that which they seemed to be?

When promoted to positions of power, there are those who deserve the opportunity to lead due to their perpetual disposition of inspiring others to be the best versions of themselves as is possible. There are others who, however, having ascended to levels of power, are unable to manifest their own full potential for good due to a blanket of narcissistic petulance and fear of losing power that embraces and informs their every action. Too often, we find ourselves at the mercy of those who have lost sight of their own humanity.

In A Lincoln Portrait, Abraham Lincoln is quoted as having said:

“The dogma of the quiet past are inadequate to the stormy present. The occasion is piled high with difficulty, and we must rise with the occasion. As our case is new, so we must think anew and act anew. We must disenthrall ourselves, and then we shall save our country.”

“It is the eternal struggle between two principles—right and wrong—throughout the world…”

Lincoln offers us quite an assignment: endeavor to not be distracted by our ingrained biases and act selflessly while choosing the path of virtue.

At the most local level, in our towns and cities, we hope that our leaders will keep their constituents’ interests in mind ahead of their own personal interests, guiding each community to success through positive means that catalyze innovation and continued growth. This chain of positive expansion is only possible through actions that engender respect, dignity and grace.

Of course, as daily life tends to usurp our immediate attention, we need regular reminders as to how we might best conduct ourselves. Religious teachings often reiterate the values of striving for a life of goodness and honesty. Service clubs sprang up in the early 20th century in the United States as organizations that codified the ideals of assisting others for the greater good.

During my tenure as Music Director for the Knoxville Symphony Orchestra (2003-2015), I received the honor of being named a Paul Harris Fellow by a local Rotary Foundation chapter. Having attended my fair share of Rotary Club meetings over the years, I have become very familiar with the Rotarians’ moral code for personal and business relationships known as the Four-Way Test:

- Is it the truth?

- Is it fair to all concerned?

- Will it build goodwill and better friendships?

- Will it be beneficial to all concerned?

Indeed, a fine barometer. Unfortunately, hypocrisy abounds in a world in which some of those whom would utter these words, or the message of these words in similar variation, might also be easily seduced to conduct themselves in ways that divert from these paths of truth and goodwill out of convenience and/or greed. I am, by no means, perfect, but I cannot fathom joyously living a life in which I knowingly defied the precepts of these honorable questions.

We like to think that we can control our environment. Indeed, we can endeavor to follow a path that is safe and true. We aspire to emulate these ideals in our homes, in our schools, in our places of worship and in our personal relationships with the hope that our microcosms will nurture the macrocosm. At times, though, in our naivete, we might find ourselves suddenly in the middle of circumstances that seem beyond our control, presenting limited choices of resolution.

I am disappointed to say that my desire to celebrate the achievements of the four presidents nobly depicted at Mount Rushmore will forever be dampened by an experience that, if anything, sheds light on the issues we must continue to discuss and the principles we must continue to uphold. I recount the following story as an example of that which happens when a community diverts from the path of truth and goodness by building its foundation on a bed of schemes, manipulation and falsehood. Such an existence breeds a virus of sorts that taints not only the city’s inhabitants but, also, anyone who might unsuspectingly come within the borders of the disease. Things may suddenly spin horribly askew but it is our strength of character and value of integrity that, employed correctly, can bring things back to center or, at the very least, open up an alternate route back to the path of the righteous.

One caveat: I acknowledge that I have been blessed with a lifetime of privilege. I can never fully appreciate the indignities encountered by the millions of people who live with but a percentage of my privilege. I relay my own experiences not as a means by which to gain solace or arrogant justice but, rather, the only way I know by which I can begin a conversation to help level the playing field.

July 17, 2007: Max and I left the Deadwood Hampton Inn at 8:30 A.M. with the intention of arriving for rehearsal at the campus of Black Hills State University in Spearfish, S.D., by 9:00. Dressed all in black as I usually am for rehearsal (it hides better the inevitable perspiration that comes with all the cardiovascular arm-waving exercise), I drove our rental car towards the highway with thoughts of organizing the rehearsal of Aaron Copland’s iconic composition, A Lincoln Portrait, but, as it turned out, my planning was moot.

Not three minutes later did I see in my rear view mirror the flashing red and blue lights of a local cruiser, flagging me down to stop just before the road transitioned to Spearfish.

“Uh-oh,” I said to my nine-year-old son, “I’m being pulled over.”

There wasn’t anywhere to stop so I needed to drive until I could find a swelling by the side of the four-lane highway. I remember gesturing in the rear-view mirror something to the effect of, “Where should I pull over?” to which the trooper behind me just waved his hands in disgust.

Once stopped, I removed my driver’s license from my wallet. When the trooper got to my rolled-down window, I asked, “Was I going too fast?” To which the trooper replied, “What—are you nuts? Going 64 in a 35? Yeah. Could I see your driver’s license?”

After handing him the license, I was asked to step out of the car. He then asked me to face the car and put both hands on the passenger’s door.

Retrieving my right hand first, he began to put handcuffs on me. “I’m arresting you for reckless driving.” I was in a state of disbelief as I witnessed fear and panic overtake my sweet son’s face.

I was led to the back of my rental car where I was told to face the police car. The trooper got into his vehicle and called in my license number. When he got out of his cruiser, he reiterated that I was being arrested for reckless driving and then informed me that DFS (Department of Family Services, I assume) might be needed to take my son.

I could see that Max was distraught in the back of our rental car as the officer went back to speak with him and calm him down. The trooper returned to me and, as he removed the handcuffs, he said, “I’ve calmed your son down and I’ve told him you’re not going to jail. Okay, here’s what we’re going to do.”

For the briefest moment, I dared to hope that he was going to let me off with just a warning. I was wrong.

Gesturing to a parking lot on the other side of the road, he said, “You’re going to pull over there and then follow me to the courthouse.”

I got back in my car, assuring Max that everything was going to be okay, pulled into the parking lot as requested, and then drove behind the cruiser back into the hotel and slot-machine mecca of Deadwood that had long ago lost any semblance of historic dignity. While on the way, I called up the youth orchestra’s manager to let him know that I had been arrested in Deadwood and, perhaps, it would be best if they began the morning with sectional rehearsals because I didn’t know how long I might be detained.

We parked side by side at the rear of the police station/court house. Max and I were led in by the trooper to a small office which the officer used to make some phone calls about my case. Trooper B. said to Max, “Your dad’s lucky you’re with him because otherwise he’d be sitting in jail right now.”

I sat in a chair in front of the small desk with Max standing tearfully beside me. The next few minutes were spent in nervous anticipation of being able to access a judge who could hear the case that morning in order that Max would not have to be separated from me overnight.

Despite the fact that I quietly harbored an underlying doubt as to the veracity of the trooper’s claim regarding the speed I had apparently achieved in my putt-putt rental car on the arterial road leading to the highway, I did what I could to utilize the situation as a teaching moment for my son, explaining the value of personal culpability for our actions.

A woman from the front office came in to tell us that the judges were all in court at the moment and hopefully, I could be seen during a recess. When she left, I asked the trooper what speed above the speed limit would have still warranted a ticket as opposed to being arrested. He said that, perhaps, 20 mph over would be the limit.

The woman came back in to say that a judge had been found who could hear my case so it could proceed shortly. She then indicated that, without meaning to put pressure on me of course, I had the option of pleading guilty now and paying a fine of approximately $500 or posting a bond which would probably be for the same amount and coming back the next morning in order to enter my plea (guilty or not guilty). Of course, if I elected to enter a not-guilty plea, they probably could not find a defense attorney who might take my case until the next day, at which point I would be locked up overnight and DFS would need to take my son.

My wife, Debbie, was not with us at this moment on the trip, as she was in Washington, D.C. at an orchestra conference. Deciding it was best not to disturb her with the details of my present quandary and not relishing my position between the proverbial rock and a hard place, I elected not to drag out the proceedings but, rather, to go through with everything right away, if possible. I asked if Max would be with me in the courtroom and they said that would not be a problem. However, they felt it best for him to go to the front office while I was being booked (the ladies up there would watch him).

Max was led away and I was brought to the booking station prior to my appearance in the courtroom. I was put through a complete routine of fingerprinting and mugshot acquisition and then was led to a row of chairs and directed to sit down. However, it was not long before the supervising officer said to me, “I need to leave for a few minutes so I need to lock you up.” What?! I said, “Seriously, I’m not going anywhere.” Despite my plea, the officer instructed me to follow him to the holding cell and suddenly, with a quick turn of a key, I was sitting in a jail cell staring at the peeling yellow paint on the cell’s bars and thinking, “This can’t really be happening. Half an hour ago, I was on my way to rehearsal and now I’m sitting in a jail cell in Deadwood, South Dakota.”

After five minutes, the officer returned and released me from the holding cell, informing me there was one more stop before we could make our way to the courtroom. In a side room I was guided in front of a furniture piece that resembled one of the kneeling “back” chairs that were all the rage in the 1980’s. Indeed, I was asked to climb aboard but, before doing so, inquired as to why this was necessary. The response was chilling.

“The judge won’t allow prisoners in his courtroom without shackles on.”

With that, I just about lost my cool and contemplated resisting beyond my verbal exclamation of, “You’ve got to be kidding, right?!” Was now the right time for me to mention that I had ninety young instrumentalists from all over the country waiting for me to lead them in preparations for a very special concert to be held at the foot of Mount Rushmore the following week? This was not the welcome wagon I had ever expected in Deadwood.

I kept my mouth shut, however, and climbed up on the device only to read the note sewn into the top portion of upholstery: “DO NOT LEAVE INMATES IN THIS DEVICE LONGER THAN TWO HOURS OR DEATH WILL ENSUE.” Very comforting, indeed.

Shackles were placed around my ankles and then, upon standing up, a chain was routed back up to connect with the wrist restraints with which I was bound in front of my chest. With enough gear attached to make sure this serial speeder was not likely to commit another traffic violation, we began making our way to the courtroom at the other end of the building.

Beginning my shuffle down a corridor, the arresting officer opened a door to that which must have been the front office. Just before entering the new room, however, I saw my son at a table with an assemblage of coloring utensils, calmly drawing a picture of his latest, most favorite superhero. Stopping in my tracks, I implored the officer to shut the door and find another path to the courtroom…which, thankfully, he did. Teaching moments be damned: I was not about to allow my son to have this vision of indignity forever seared in his memory.

We made our way upstairs to the courtroom and while I was ushered into the defendants’ pews, I observed all of the manifestations of the court assemble in an almost magical fashion. Here was the court reporter, there was the Assistant District Attorney, next to me was my dear arresting trooper and then, without hesitation, the judge took his place. We rose with requisite respect and then, as my case seemed to be the only one being heard at the moment, the judge addressed me directly.

“Mr. Richman, have you read the complaint against you” he inquired.

I contemplated the idea of telling my entire life’s story and why it was that I had found myself to be in the clutches of the authorities in Deadwood, SD, as well as the cavalcade of indignities that had since befallen me.

Instead, I just replied, “Yes.”

“And how do you plead?”

I squelched the urge to blurt out a sarcastic inquiry as to what manner of bleeping choices did I actually have, instead answering with great restraint, “Guilty.”

The judge turned to the ADA and asked her what the fine was for my particular violation. With her answer of “$300,” the judge proceeded to pronounce his sentence.

“Mr. Richman, for the crime of reckless driving, you are sentenced to serve ten days’ incarceration. However, I grant you one year’s probation in lieu of that sentence in addition to payment of the $300 fine. Should you violate the law again, you will be required to return and serve the full length of your sentence. Do you understand these terms?”

“Yes.”

“Pay your fine and you will be released.”

Trooper B. led me out of the courtroom and back downstairs to the cashier. I explained to him that I had left my wallet in the car and would need to retrieve it before paying the fine. With this new information, I was guided to the front door of the police station.

“Could you please take off the shackles?” I asked politely.

“No.”

“Really? I need to be able to get into my car…”

Once it became clear no change in the status of my bounds was impending, I was subjected to yet one more debasement as I was now obliged to waddle to the parking lot in full restraints. Note: if you ever have the opportunity to attempt stepping off a curb in shackles, I suggest you make sure someone is nearby to catch you when you fall down. After opening my car and awkwardly retrieving my wallet, I was led back inside to the cashier.

Within minutes, I had paid the fine, was released from the handcuffs and shackles, collected my son and, soon seated at a table in the local Burger King, I looked across the table at my beautiful boy and asked, “What the hell just happened?”

Rehearsal that afternoon went well, especially due to the unexpected re-arrangement of sectional rehearsals earlier that morning. Our concert later the next week at the base of Mount Rushmore was a resounding success, with the four presidents offering their quiet but steady approval. My son, however, had been traumatized by the experience and it affected him for a number of years afterwards.

It is my hope that the reverberating strains of powerful orchestral music as produced by the assemblage of generous, respectful and kind young artists continue to echo in the Black Hills of South Dakota, working to drown out the dissonant cacophony of soulless power mongers howling in their daily manipulations and petty contrivances. I do not immediately desire a return visit to see if this hoped-for evolution has occurred, as the pessimist in me suspects it would not be the case. If this is the sort of thing that can happen to a well-intentioned conductor bringing music and nearly one hundred young people to South Dakota for the first time, I can only imagine what happens in the cities there on a regular basis.

I also wonder what the Rotary Club in Spearfish-Northern Black Hills would think of all this.

I must make it clear that, despite the clear abuse of power and unnecessary actions taken by the individuals mentioned above, I have always been, and continue to be, in a state of awe and great appreciation of those who serve our communities as members of the police force and all first responder organizations domestically and internationally. We must continue to support those who sacrifice so much daily to make it possible for us to live with the freedoms we so cherish at home and in our communities. At the very least, I would hope my story might initiate a dialogue with those that find it more important to generate income by catching unsuspecting tourists with traumatizing speed traps than to look within to find even greater values worth cultivating for the long-term sustenance and success of the local community. This would be the true teaching moment from which we could all learn.

“It is the eternal struggle between two principles—right and wrong—throughout the world…”