During the summer of 1983, I found myself happily ensconced in my second season as a violinist and conducting student in the Los Angeles Philharmonic Institute. Orchestral rehearsals and masterclasses were held on the campus of Cal State University Northridge, with the opportunity to perform on the impressive stage of the Hollywood Bowl. I was continuing my violin studies with Alexander Treger, concertmaster for the LA Philharmonic, who had just valiantly seen me through my junior recital at UCLA—despite my penchant for participating in everything else the music department had to offer except for productive time in the practice rooms.

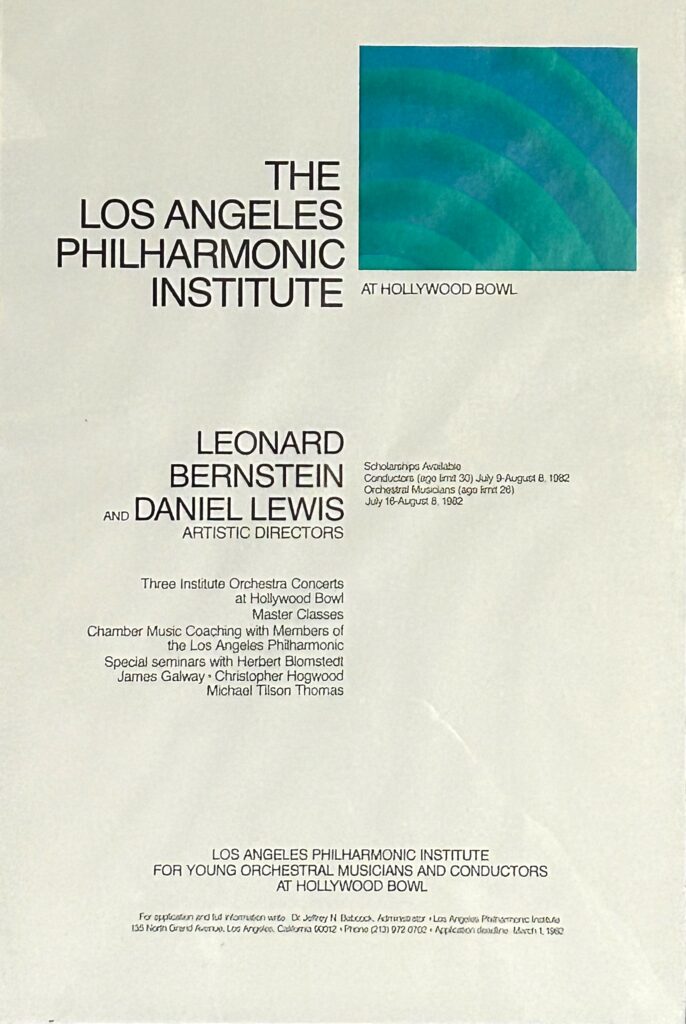

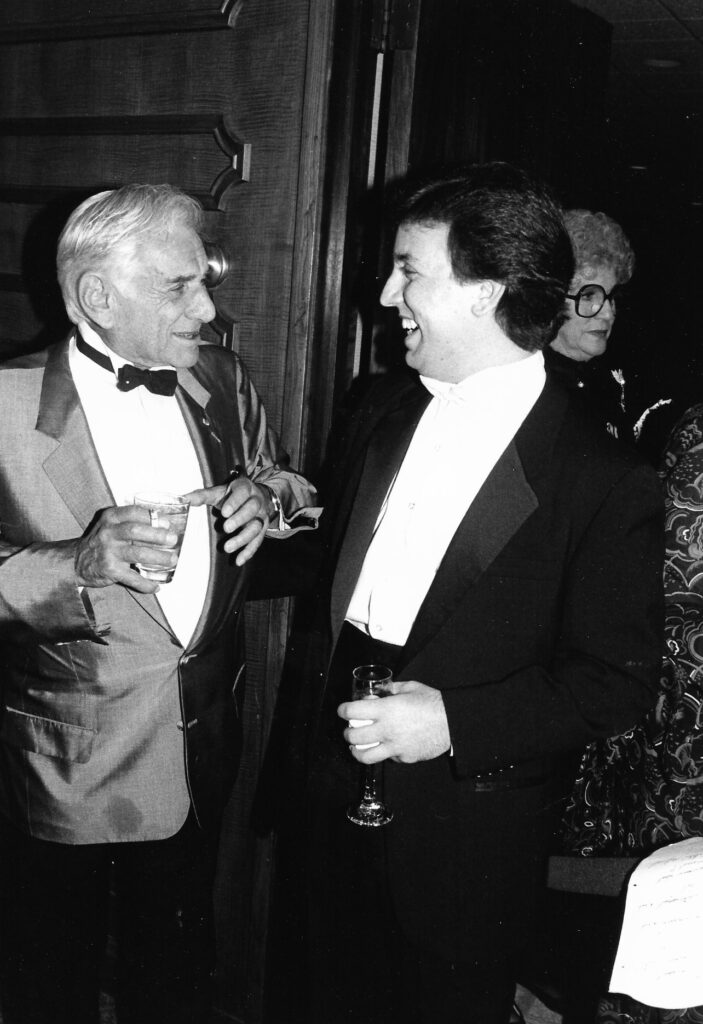

Ernest Fleischmann, executive director for the LA Phil, had corralled Leonard Bernstein into once more serving as the Institute’s Artistic Director, building upon the successful launch of the previous inaugural season. Being nineteen years old and low on the totem pole of experience, I had not been chosen as one of the three conducting fellows who would lead the Institute Orchestra in concert. I was, however, able to study conducting with the Institute’s faculty which included Michael Tilson Thomas and Neal Stulberg. Those of us in this larger pool of conducting “fellas” would each vie for opportunities to conduct in masterclasses with two pianists manifesting the full orchestral scores or, even more prized, time on the podium in front of the student orchestra. Consequently, it was on the bright Monday afternoon of August 15, 1983 that my life changed just by raising my hand.

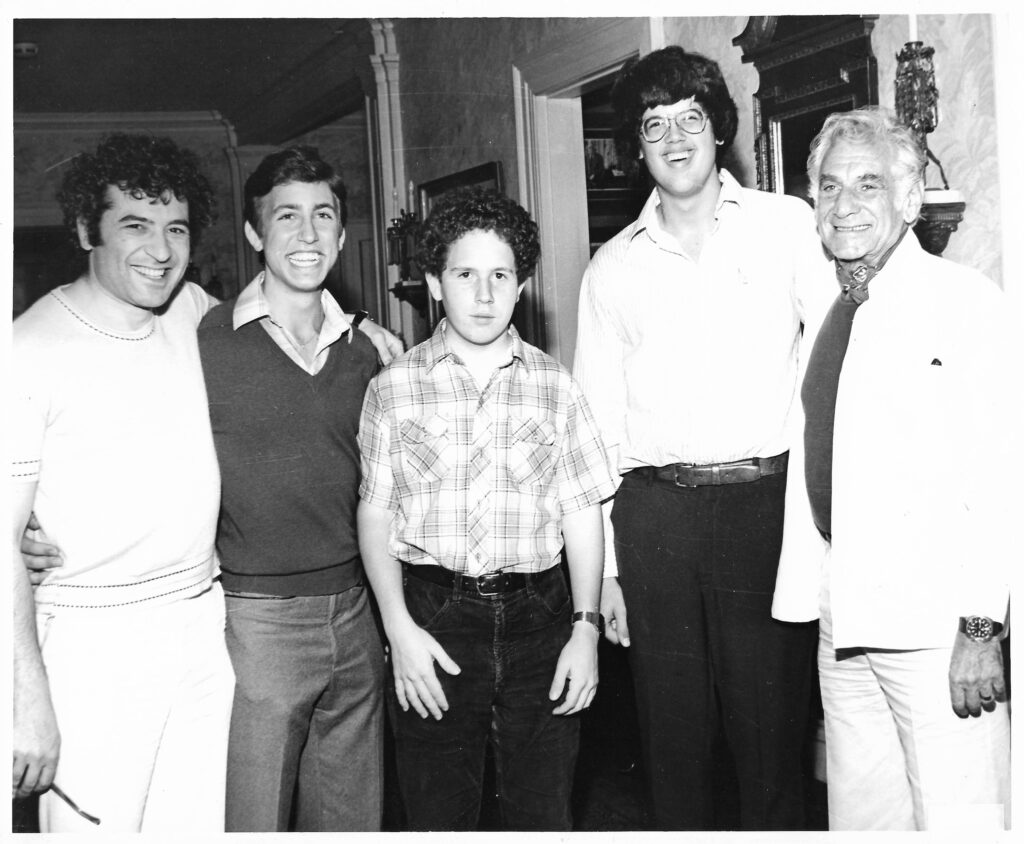

I had first met Leonard Bernstein in 1980 at Seranak, the summer home named for Serge and Natalie Koussevitzky just outside the campus of Tanglewood in the rolling Berkshire mountains of Massachusetts. That summer, at the age of sixteen, I was studying conducting with Victor Yampolsky, conductor of the Boston University Tanglewood Institute orchestra. Maestro Yampolsky assigned me to conduct Brahms’ Academic Festival Overture, facilitating my conducting debut at the annual Tanglewood On Parade celebration taking place later that month. The three BUTI conducting students (Daniel Shapiro, Tzimon Barto and myself) were invited to an afternoon lunch at Seranak along with the Tanglewood Festival Conducting Fellows. Through my father’s work as an actor in Los Angeles, I had met numerous luminaries in theatre and film—but this lunch at Seranak would be my first exposure to a whole other echelon of living legends.

Two years later, I was accepted as a conducting student in the launch of the Los Angeles Philharmonic’s manifestation of a “Tanglewood West”: the Los Angeles Philharmonic Institute. Leonard Bernstein, as Artistic Director, was bringing the legacy of Tanglewood to the west coast so hopes were high for the success of this new four-week festival. My interactions with the maestro that summer were mostly limited to orchestra rehearsals and various social get-togethers arranged for the conducting class (my surreal poolside encounter with Danny Kaye at Bernstein’s rented home will be the subject of a separate article!).

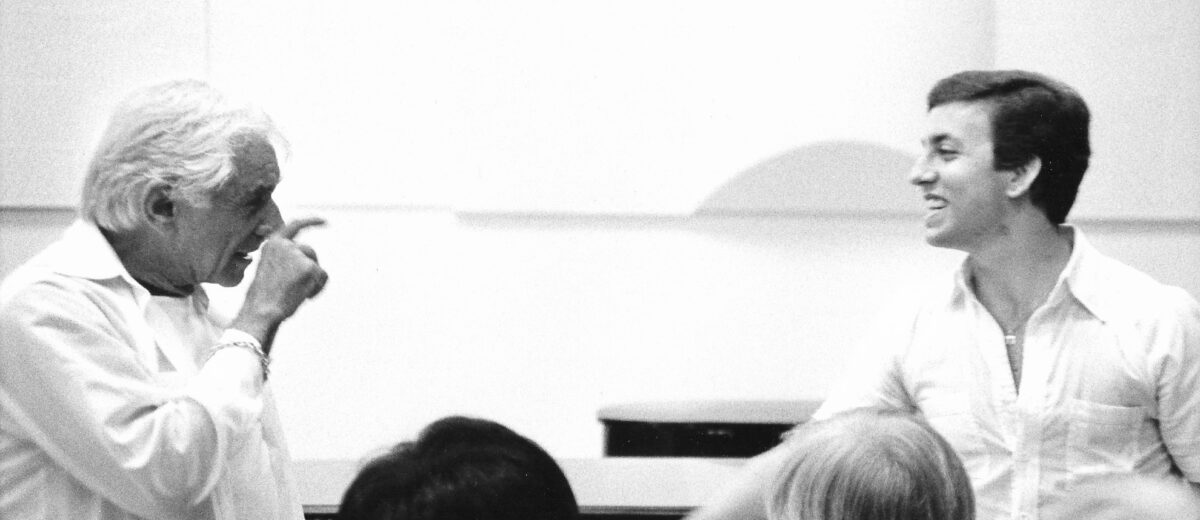

During the following summer’s Institute, Bernstein was still in the throes of completing his opera, A Quiet Place. However, every hour of his time in Los Angeles was filled with rehearsals and performances with the Los Angeles Philharmonic and the LA Philharmonic Institute Orchestra as well as masterclasses and numerous social events. While preparing for an upcoming performance of Brahms’ 4th symphony with the Institute Orchestra, the music of Brahms was foremost on Bernstein’s mind. Consequently, he offered a masterclass to the conducting “fellas” with the focal piece being the Academic Festival Overture. As soon as the maestro asked for volunteer participants, I leaped at the opportunity! Squelching my shaking knees, I took my place in front of the two pianos, hoping the memory of conducting the work three years prior would support my bold teenage bravado… and what ensued was a 50-minute masterclass in music, life and humanity.

1983 Masterclass with Leonard Bernstein:

THE MASTERCLASS

Transcription by Lucas Richman

Leonard Bernstein (LB)

Lucas Richman (LR)

Michael Tilson Thomas (MTT), Neal Stulberg – piano

Los Angeles Philharmonic Institute at Cal State University Northridge, 1983

Brahms – Academic Festival Overture

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

LR – How about going back like five bars before that forte?

LB – Great.

Music

LB – What did he do?

CS (Conducting Student) – He went up, instead of two downs.

LB – No—he did both!

Laughter

LB – He did both things. Because he went “Down, bomp.” With his right hand he gave another upbeat…no…he did–with his right hand he did the beatings…Down, Bomp! Then, what did he do? Up, Bomp! Da-Duh! That’s with the right hand. And then with the left hand, while he was doing that, he did “That”: Beem, Bomp—Da-Duh! That’s hard to do…! Did I do it? Did you see the two things at once? Alright—it’s some little like this (pats head and rubs tummy). Alright—it’s a little schizoid…How would you like to start from the beginning and show everybody how much you assimilate from this poor man’s subjection to torture?

Music

LB – Excuse me…I don’t think the orchestra’s going to start together. I don’t think we, kids, in the orchestra are going to start together.

Music

LB – Think we’ll start together? I still don’t. What is needed?

CS – I think he’s pausing a little bit on the upbeat. He needs to just go right up and down, giving the tempo that he wants.

LR – Giving the inner beat?

LB – Some kind of inner beat…even if it’s just stopping to get it to…um…I hate to tell you what to do in a physiological way because that’s a very bad way to learn conducting—is to learn gestures. But the feeling of, “…And…(demonstrates)…” Whatever I did… “…And…(demonstrates)…” Nobody can do that. Even though that, whatever I did, seems to be, now that I look at it, on the way to the downbeat, right? It’s going down: “Two-and One!” That’s the better way.

Music

LB – I’ll tell you: I would have played on that inner beat…and others wouldn’t have. And then we’d have to get on that. The point is to make that little inner beat so small that no one can play on it. Look: “and…ONE! and…ONE!” It’s just…I don’t know…whatever I did, do something like it.

Music

LB – Hmm…all right, all right….just go.

Music

LB – (over music) The rests!

Music

LB – (over music) That’s good…

LB – Very good—very good! I won’t go back over all the other stuff. But just at this first forte: “Ba-bum—ba-bum”! Can you make those inner indications tighter—shorter—more rhythmic? Because that’s what it’s all about…it’s about “Dot-dum…dot-dum…dot-dum”…those little rests which are a syncopation, right? “Dot…dot-dum…” Just—“Dot…dot-dum…dot-dum”…I’m hardly doing anything…but what…minimize it. But make it…by minimizing it, you make it even more effective and clearer. Okay? Just before the…

LR – Do you mind…the two half notes.

Music

LB – (singing over music) …with heart and hand salute…

LB – (over music) …And…And…And!

LB – Do that again… you lost concentration. When you got fast you lost concentration. But then, right here, you didn’t know quite what was happening. (sings) It’s a beautiful little lead-in to the …to the second…subject.

LR – How about 107…106?

Music

LB – You’re going lose those eighths notes. They’re just going to get erased. It’s very secret, right?…Even though it’s moving slowly (sings)…that’s what we’re going to get (sings)…which is the heart and soul of Brahms. Inner beats. Inner beats is…inner…the innards of beats. It’s what Koussevitsky used to say when I was…your age…really…twenty years old…whatever it is…He’d say, “My dear, it is what is BETWEEN the beats.” And he says if you…and he was so right! I mean…and Reiner said the same thing, of course. Once you beat, you’re dead. It’s too late to do anything. The nature of the beat makes no never mind to anybody in the orchestra. You could die with your secret—they would never know. It’s the preparation: every beat and every bar…and everything is in the ups and in the…the way one beat GOES to an up. Now, Koussevitsky used to line us up in a room and, gets some little batons like this–Reiner’s were like that (indicating wide span)—and we’d have to go…while he counted: “Imagine 4:4 Andante, no music, no particular piece.” “Und,” he would say (instead of “and”). “Und vohn and two…Und three and—you’re beginning to get the idea starting English—and one and two and…then we’d have to do this by the hour! Just so he could get his point across…we only did it with him and just to get a 4:4 thing out of him and Andante. Once you do two, it’s too late. So, it’s how you get from two to three…and are there any other notes on the way and what comes in…and life is going on in here (gestures to the score), in this amazing swamp…this chaotic swamp, which an order has been brought to. And that’s what you’ve got to lead us through—is the order of this otherwise swampage, right. Okay?

LR – Same place.

LB – (singing) You can go from side to side—it doesn’t have to go up and down! In fact, it’s a rather…like a cheat really, too, isn’t it? (singing) That’s a right and left; it’s not (demonstrates)…that’s a…that’s broken sound, right?

Music

LB – (over music) …that’s beautiful…nice! Just like that…give time…

LB – Now…we’ve really reached the second subject. It’s taken all this time. All those false second subjects are all preparation, right? Because they’re student tunes which is what this piece is based on, right? You all know that. I don’t have to tell you about that. Breslau, doctorate…So, he uses student tunes and, in order to be able to pile them on and…make a climax, with the one against the other, ending apropos of nothing at all, in Gaudeamus Igitur, as musically appropriate, apropos of the University, yes, but in order to make these kind of points he chose different kinds of tunes, each time falsely leading you to believe that you’d arrived but you haven’t ‘cause you’re still…you are in F, you went back to C…you’ve not reached the dominant. Now you HAVE reached the dominant but it’s not a real dominant, right? But it is the only…that’s as dominant as you’re going to get, which is the mediant. Okay? And so we know: now we’ve changed key and we know we’re in a sonata form finally. Okay. So that you’ve got to show us also. Go from…(sings)

LR – E? Pickups.

Music

LB – Now, especially here…here you’ve got to conduct those inner beats even more clearly than ever—even give a little extra time to–here I will allow you…what do you kids calling: “two clicks down on the metronome”? (sings)…because now you’re coming to the real…right? Now come from…yeah.

LR – Pickup to four before the change of key.

Music

LB – Sorry, I missed it—I’m missed it—I’m sorry.

Music

LB – You see why I’m allowing you to increase this?

LR – Because we’re arriving at…

LB – Because the eighth notes are big notes now—they’re big—bigger eighth notes than we’ve had. They’re not just important to hear the eighth notes but they are all supporting them…(sings)

LR – So we need more on the first measure…

LB – (sings)

LR – One bar before…

Music

LB – (joking over music) …that’s the not the way I’m used to hearing it…

LB – They need time to make that diminuendo…when we…when we now go into G which is, finally, thank God, the dominant and we’re really in the second theme…(sings)…they need time to make that…to make the diminuendo and still get the full value of the eighth. So there you’re two clicks down. Whatever that means from…if you start at 80 to a half-note, then let’s say you can do 76. All right?

LR – 127 please…

LB – There are, of course, are those who say you could do 60 here. Now Bruno Walter always slowed down to something twenty degrees less than imaginable in the second subject of almost every classical symphony…he did. That was…a way of doing it. These days we’re a little more moderate…but let’s take advantage: put yourself in Brahms’ shoes. What was he feeling with…(sings)? Okay.

Music

LB – (over music) …it’s a little exaggerated but okay…

LB – Now that’s–all right– that’s bad—that’s total exaggeration. Now, see if you can do that and sort of remain on your tightrope, ’cause there you fell off and were in a whole other field.

LR – Same place…

Music

LB – Did you hear? Did you hear the eighth notes getting broader and broader…each one on the pianos? Nobody told them to do that. But he did it—he showed them. (demonstrates) The last…it all worked out exactly—and it was intended. That’s what I wanted to tell you.

Music

LB – (over music) …lovely…too much…diminuendo…just give it very little…it’s time…not every time…every other time…do it again…not a lot.

LR – How about one before F?

LB – You know what I mean? You all–guys all know what I mean?

Music

LB – It’s too much…too much…it’s right here (sings)…it’s just letting the diminuendo happen. In other words, the inner beat becomes longer—not in time but in space, right? (demonstrates)

LR – Same…one before?

LB – (over music) …that’s it…everybody’s playing offbeats…no division here…a smooth cadence…And!

Music

LB – Now…you have syncopation which is…where is this place? Right—you have syncopations going on in the strings, right? (demonstrates) One of the hardest things to do is to have them be together. And one of the easiest ways of cogging the step tongue is to give some kind of…what Reiner used to call…the “ricochet.” A bounce. It’s just…(demonstrates)…I don’t know what I’m even doing but I know that, if I did this, the strings would be playing the offbeats. (demonstrates). Something happens…it’s wrist-wise. (demonstrates) And there’s not very much difference between one and two. It’s not ONE-TWO-ONE. It’s…I know what it is! It’s that all the beats are up! And then they will play. You see, it’s not ONE-TWO…it’s one-two…(demonstrates)…you see what I’m doing? I don’t.

LR – Yeah…

LB – Okay? It’s the sense of…(demonstrates)

LR – How about four before?

LB – (sings)

Music

LB – We were actually taught this. We were taught movements by Reiner, with his very long baton. So that, by barely moving it, the end of the baton is moving a lot. That was the fabulous, legendary, tip of the Reiner baton, right? ‘Cause you can stand and do this…(demonstrates) and… miracles happen. And they WERE miracles because what would happen would be this little but…it’s…your wrist is staying…yah! So do nothing except…(demonstrates)…and feel…that’s good…now you moved your arm…just with the wrist. Just…(demonstrates)…I don’t know what it is—but they…it works!

LR – Right on it.

Music

LB – (over music) Great!…Great!

LB – Go from a few bars before that so we can see the real change. And what he did there was real good, you see, as when he needed to do something else, he kept this thing (demonstrates)…this Brahms jazz going here (demonstrates)…and when he needed something else, he used his left hand for it. It’s just what life’s about.

LR – Four before…

LB – That’s being music. In this case, you have to beat time with one hand because it’s really about—there’s nothing much going on except this “I think it must be Santa Claus” song. But, there IS something else going on and you use your left hand for it. Okay.

Music

LB – (over music)…don’t move your forearm…only your wrist…only your hand…

LB – Okay, that’s all—you’re going to confuse the orchestra because you’re conducting too many beats. We don’t need all that. That’s not conducting the music. You’re conducting one-two, one-two. The music isn’t going one-two, one-two. It’s going one-one-one. Let’s see you do it. From the…umm…from the subito forte.

LR – Fortissimo…

Music

LB – So, who’s playing those triplets you just heard?

LR – The horn players.

LB – I know you know…you’ve got a score in front of you. I want to ask the others.

CS – Third horn…Third and fourth.

LB – Second pair. (sings) It’s a wonderful place. Okay. Very magical.

LR – Same?

LB – The same.

Music

LB – (over music)…Like Rheingold!…Do it like…a divided one. One and…That’s it. I didn’t mean divided one. A one something inner…Patterns of beat…Great! Great! God, what an exciting piece this is turning out to be!

(Laughter)

LB – What I would love to see is in that lyrical section of 2:4—you know where I told you just beat one…but one with something in it. (demonstrates) What I would love to add to your problems now is do all that plus show us the bar phrase. I mean, if it’s a four-bar phrase. You’re in one. One is awful.

LR – Shape the planet (referring to something LB said earlier in the masterclass).

(Laughter)

LB – No…shape the music. Don’t shape—he shaped it. You know what. You’re his servant. That’s what—the only thing we’re here for is to make this come alive…(demonstrates) Now…(demonstrates) Where you sense a four-bar phrase, show it! The orchestra eats it up! You have no idea how they play if you…for example, the four bars of triplets before Santa Claus comes out, right? You play…(demonstrates) It’s okay—they’ll play all right…(demonstrates) A great start in life if you’re Santa Claus. But, if you play…(demonstrates) If—if you conduct it like…conduct four beats with subdividing…(demonstrates) Two…(demonstrates) Three…(demonstrates) Four…And! …(demonstrates) That’s an “and” within an “and” then. The orchestra will swell with you on the third bar and diminish with you and become staccato in the fourth bar, which is what you want, right?…(demonstrates) There’s a natural opening up on three which happens to coincide with the natural opening up of where three is in that bodily manifestation of it, so…(demonstrates) Four and…(demonstrates) Right? Try that and then, when you come to the lyrical 2:4, see if you can re-apply what I just told you about this cadence.

LR – Four before 157 where the triplets…

LB – Excuse me. Let me ask: who is committed…I don’t want to…or is entitled to perform during this? I’m supposed to get to know all of you, right? But not all today, right? How many are expecting to…I’m just trying to adjust the clock…the time. Rin-tin-tin-toul?

RR (Richard Rintoul) – I would like to!

LB – Nobody else is…

MTT – This clock is off…but you have a watch so you can refer…

LB – That clock is very slow, yes. Yeah, it’s twenty minutes of four…and that means we have a sort of fat hour, then. I just don’t want to pass over anybody if…if you were…if time was pledged to you today. Michael?

MTT – Is there anyone who’s not going to be working with the orchestra for the Wednesday set with orchestra that would like to do something now?

LB – I just want to be…you’d like to do something. You would? Now…now the hands go up! Well, I mean anybody who was pledged to do something today—somebody that I am committed to hearing today that I might not otherwise hear. All right—let’s see how it goes. I’ll figure it out. ‘Cause I want to get you back…and pick up from where you were earlier. You’re a very quick study.

CS – Pardon me?

LB – You’re a very quick study. That’s why I would take the chance bringing you back to pick up some of this. All right, go! …(sings)…like Brahms’ clarinet trio—it’s in all of that chamber music of Brahms. The wonderful, warm things that do that…and that…and that…

Music

LB – (over music) Wrist! Wrist! I’m trying to get you to do this…

LB – I don’t know…I don’t want to hold your hand—one of those things that conducting teachers do—it’s worse than music appreciation…it’s so horrible, but…in this case, this is just so valuable to learn, this Reinerism. No…but make it bounce. And they’re all ups and they’re all ones. Only, the one-one is a little lower than the two-one…and they’re all bounces so you see the “ands” within the “ands.” Okay. Now why am I not asking him to do this in…in bar phrases? …(demonstrates) I mean, wouldn’t that be helpful?

LR – No.

LB – No. Why?

LR – Well, for one thing…

LB – Because here, for the first time, you do want to get really a bar by bar because that’s the nature of the song. The song does that. It’s a mechanical…a mechanical clock, where the bird pops out and sings…(sings)…it’s that kind of tune.

MTT – And Chico Marx is playing the bass line.

(Laughter)

LB – Yeah…right. And Harpo’s filling in with the afterbeats.

Music

LB – (over music) You see how nice that is? Loosen up the wrist…And!…And!…Take care of those celli who are having to play bar by bar, too…now, pure lyricism…Two…Three…Four…(sings)…One…Two…Three…Four…And…And!

LB – Now, would you have done that all in fours and added a fifth bar at the end? Or would you have started a bar later to make the fours? And if so, where? What did I say: would you have started…earlier? Did I say earlier? I heard myself say earlier…

CS – You said later.

LB – I said later?

CS – I think so…

LB – I think I did–I mean earlier. I’m still in a state of shock. When you come to this…(demonstrates) When I go in two bar phrases…(demonstrates) If you keep doing four, you’re going to have to add a beat rather than five here…so where do you think you should start the series of four?

LR – You mean a new four?

LB – Right—so where are you going to start? Well, the tune doesn’t start till…(sings)…the tune that asks to be in four…(sings)…at H…(demonstrates) So, obviously, the fifth bar of H is the extra bar, isn’t it? If you count H as a down bar. You see, this isn’t just a little tideway station. It’s very important because there are so many pieces that you’re going to run into in the course of your musical lives which aren’t in one. For example, all Strauss waltzes…for example, codas of various things that are in 2:4 but can be done in one. The end of Brahms’ 4th, for that matter, right? The Piu Mosso in the Passacaglia. And, in all these “one” type—the finale of Schumann 2nd, for example—that’s a case in point. Do you know this symphony? It’s a symphony that’s always been…rarely played because it had a weak finale. This is the received wisdom of the world—WAS! It isn’t anymore—everybody plays it now because a secret has been found. The last movement is in Alla Breve but it’s so fast that it has to be conducted—most of it–in one. And there is no indication anywhere of where the Down beat—one—is. See: each bar is a beat, and they go in groups of three and four—or usually four. Right? Four bar phrases…but, what you have to know—you don’t necessarily even have to conduct four. I mean, that’s a conceit of mine—a whim. See…if you want. But, you have to feel it…and then, when there’s a three or a five (as here) you have to be able to show it. In this finale of Schumann’s 4th, if you don’t get it…let’s say—Schumann’s 2nd I mean—if you don’t get the point of where the downbeat line is…so that one minute into this finale, forget it—forget the rest of the finale: it all sounds wrong. And that’s why it was always called a weak finale because…because conductors didn’t understand how to conduct it. And the only thing you have to know about is the point at which “one” really happens. Let’s see if I can remember—could you remember if I just sang it to you? The second subject is the danger point…(demonstrates) Nothing in the world sounds more four-square than that, right? …(demonstrates) You’d think those phrase bars would indicate everything. …(demonstrates) But, no—that’s wrong! And, if you start first time doing that, you’ll come out wrong. All the way—you’ll be wrong right till the final bar. Because it happens to be, “One”… (demonstrates) It has to start on Two! On the second of the four-bar phrase. And, if it doesn’t, everything else is going to be wrong. Isn’t that incredible?! I mean, isn’t that incredible that no notational system has ever been devised, hadn’t even been devised by 1840 (whatever it was)…50—to show a downbeat phrase when you’re in one. The downbeat of the phrase. And, the same thing is true here. So you’re going H—if you conceive of H as a “one”—as the downbeat of a series of ones—which, I guess, there’s no other way to conceive it, right? One…(sings)…those are two pairs of bars, right? Then, you can’t get…(sings) So, obviously, you’ve got a little extra bar in there, the fifth bar of H. Because…(sings) is obviously four bars that belong together. So, what are you going to do if you’re in one?

LR – Add another up.

LB – Another up…(demonstrates) So, what you could do…all right—that would be all right. It would be clearer if you did “Two” and “Three” (demonstrates).

LR – Oh, I see.

LB – It doesn’t matter because they’re all kind of equal. It’s latitudinal music again…(demonstrates) And you have this thing going anyway. But, as long as you know in your head that that fifth bar is an upbeat bar, then the rest can come in four. Go ahead. So, you were doing the other way for it and I was encouraging you to show you how it comes out wrong. Did you all see that? When it came to the bar before…(sings)…it’s in the…he was doing a “one”! Instead of which, that’s an upbeat bar to the return of the Alla Breve. Okay? Now show us your stuff, Lucas. How old are you now—nineteen instead of eighteen?

LR – Nineteen.

LB – It’s time.

(Business with attempting to toss his drinking cup off camera)

LB – Not too clean. Suddenly…nobody drinks anymore. Now…yes, H…just somewhere at H.

LR – Eight before?

LB – (over music) Show…inside…

LB – That’s far too lyrical for this kind of march that’s going on here…(demonstrates) You’re not going to get…(demonstrates) Go from the…(sings) return to the Alla Breve.

Music

LB – Okay…(acknowledging receipt of drink) Thank you! That mysterious…still center…You know, every Brahms movement has a still center in it like the eye of a hurricane where everything is just poised and hanging, hovering…and you don’t know what’s going to happen—and something marvelous always happens. Who would venture to guess what the still point is in the coda of Brahms’ 4th which we’re going to be doing this week coming up? Showing no hands…okay, let’s stay with this.

Music

LB – Atta-baby…(sings)…of all things–and we’re flying again! It’s just amazing…anyway, this is the still center of this one. And let’s see if you can show it—where it almost comes to a complete stop. Complete halt…(sings)…indeterminate harmonically, rhythmically—it’s all ambiguous…(demonstrates) And you’re safe.

LR – “I”?

Music

LB – (Over music)…And…And!…And…One, two—rhythmic—and with the jazz…and…

LB – You’re going to waste your energy there. What they need is four beats in a bar at this point. (sings) Isn’t that where the fiddles are playing tremolo way up in the impossibly high positions, right? Anyway…(demonstrates) Then, again…(demonstrates) They’re never together at that point because you’re going like this as though it were all bat and butterfly…(demonstrates) Very powerful moment. And you don’t have to do “four”; you could do “one-and-two” I was going to say is “four”—I just feel really “four.” But that’s very personal. Do what you feel. Do what you feel that will help the orchestra play it…(sings)…four bow strokes to the quarter note.

LR – Four before “K”…

Music

LB – They need the subdivision in those—what you would call a subdivision—you know, the inner beat. Until they reach this…(demonstrates) And then you’re really back in the broad “two.” The second time on the (demonstrates)…

LR – 281? Yeah.

LB – (Over music)…In four!…Three and Four and One and Two…

LB – Okay—very good, Lucas. Very, very good! I mean, he’s only nineteen…

Copyright @ LeDor Publishing, 2023